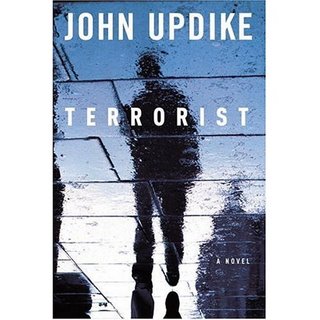

Terrorist by John Updike

It's likely that, as the 9/11 anniversary approaches, that subject will appear here once or twice. Coincidentally, or not so, depending on on your view of co-inky-dinks, I completed John Updike's Terrorist last week, two hours before we discussed it in book club. Melanie had suggested this back in June, and I leap-frogged over the July assignment (maybe subject for a later post).

Anyway, Terrorist was the book, and here I am writing about it, less than a week before you-know-what. And, Kurt Vonnegut would say, so it goes.

When all is said and done, I enjoyed the book. In Ebertese, I give it a thumbs up, but warmly and not necessarily enthusiastically. That may sound like a loaded review, but the narrative left me wanting something at the end. Nonetheless, the journey to that end was interesting and riveting.

The main character is a New Jersey high school senior who is a student of Islam. He has an absent father and this void is filled by his love and devotion to Allah. It is not an unsympathetic view, and Updike weaves his life together with that of the school guidance counselor, a Jew, who becomes connected even further in a rather Updikean way.

Check it out...definitely a good read for today's zeitgeist. If you don't want my opinion, check these quotes:

Unlike every other novelist looking over his shoulder at 9/11—an Ian McEwan, a Reynolds Price, a Jay McInerney, a Jonathan Safran Foer—Updike isn’t writing from the victim’s point of view. He guesses instead at unhinging excruciations. Finally, Terrorist has to be read as part of an accumulating literature in which serious novelists have tried to grope their way into the mind of the ultra, a literature that began with Dostoyevsky, Joseph Conrad, and André Malraux and continues with Don DeLillo, Richard Powers, and Salman Rushdie, trying to explain the phenomenon of what Victor Serge called “the lunatic of one idea,” as he shape-shifts from Belfast to Beirut to Jakarta to lower Manhattan, from skyjacking jumbo jets to bombing abortion clinics, from Pol Pot to Shining Path. Terrorists and torturers tend to be more interesting in novels, where they have complicated rationales, than they are in banal person. -- John Leonard, in New York magazine

or

In theory Mr. Updike's shopworn new novel, "Terrorist," not only gives him an opportunity to address a thoroughly topical subject but also represents an effort to stretch his imagination — to try to boldly go where he has never gone before, as he did with considerable élan in his African novel, "The Coup" (1978), and with decidedly less happy results in "Brazil," his misbegotten 1994 variation of the Tristan and Iseult legend.

At the same time, it offers Mr. Updike a chance to explore some of his perennial themes from a different angle: to look at the sexually permissive mores that his other characters have embraced through the disapproving eyes of an ascetic, religious man, and to contemplate this man's absolute and unwavering faith, which is so unlike the existential doubts and tentative yearnings for salvation evinced by Mr. Updike's earlier creations.

Unfortunately, the would-be terrorist in this novel turns out to be a completely unbelievable individual: more robot than human being and such a cliché that the reader cannot help suspecting that Mr. Updike found the idea of such a person so incomprehensible that he at some point abandoned any earnest attempt to depict his inner life and settled instead for giving us a static, one-dimensional stereotype.

"Terrorist" possesses none of the metaphysical depth of classic novelistic musings on revolutionaries like "The Secret Agent," "The Possessed" or "The Princess Casamassima," and none of the staccato, sociological brilliance of more recent fictional forays into this territory, like Don DeLillo's "Mao II." --Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times

Kakutani is a notoriously difficult critic to please. I like John Leonard, so I am apt to side with blurb one. Either way, take a gander.

No comments:

Post a Comment